The 49ers offensive line may simultaneously represesent the team's most glaring question mark and the team's best hope for better offensive production. Colin Kaepernick has shown that he can produce yards and points when he has consistently reliable protection, and the team appears to have acquired a stable of talented backs that can excell in an offense that appears to be moving toward an emphasis on zone running.

Since Alex Gibbs retired from coaching, three names are frequently mentioned as the best coaches of the zone blocking scheme (ZBS): Tom Cable, Chris Foerster, and Mike Solari. Of the last two names, one is the new 49ers OL coach, and the other is the outgoing 49ers OL coach. Mike Solari put in his assistant OL coach under 49ers and ZBS legend Bob McKittrick. He installed some occasionally-used zone concepts with the 49ers, but the offensive play calling was dominated by power runs that suited the large, powerful linemen on the roster. Chris Foerster helped establish a very successful running game with the Redskins before coming back to the 49ers, where he had previously served as the OL coach in the 2008 and 2009 seasons. Since many 49er fans remember the 2008 and 2009 seasons with frustration, it is reasonable to wonder what Foerster will bring to the 49ers in his current term.

Offensive lines are judged by the holes they open for the running game and the protection they provide in the passing game. It seems fair that a discussion regarding an offensive line coach should begin with a look at the rushing yards and sacks allowed attributed to the offenses they coach. Chris Foerster has most recently coached the offensive lines for the Redskins (2010-2014), 49ers (2008-2009), and Ravens (2006-2007). We'll look at each situation individually to try and assess Foerster's influence.

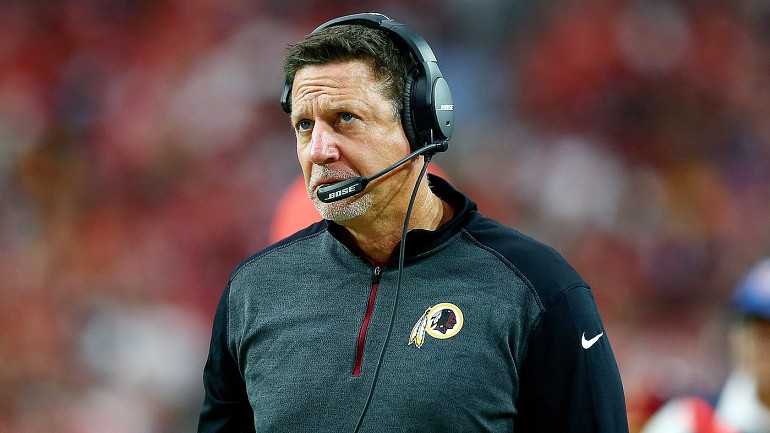

Geoff Burke-USA TODAY Sports

Redskins (2010-2014): In 2009, the Redskins were the 27th ranked rushing offense in the league and with the 29th yards per carry in the league. They allowed 46 sacks (28th in the league in pass protection) with 533 passing attempts. When Shanahan was hired in 2010, he brought in the zone blocking scheme and Foerster.

The Redskins were the 30th ranked rushing offense in 2010, and they again allowed 46 sacks (again 28th) in 2010. In 2011, they had the 25th ranked rushing offense and surrendered 41 sacks (22nd). In 2012, the Redskins ran for 2709 yards (1st in the NFL) and gave up 33 sacks (12th). In 2013 they produced 2164 yards on the ground (5th) and allowed 43 sacks (19th). In 2014, they ran for 1691 yards (19th) and gave up 58 sacks (31st).

49ers (2008-2009): In 2007, the year before Foerster arrived, the 49ers were 27th in rushing and gave up 55 sacks (tied for 31st). In Foerster's first year (2008), the 49ers ran for 1599 yards (27th again) and surrendered another 55 sacks (last). In 2009, the 49ers amassed 1600 rushing yards (25th) and allowed 40 sacks (20th).

Ravens (2006-2007): Prior to Foerster's arrival, the Ravens ran for 1605 yards (21st) and allowed 36 sacks (27th). In 2006, Foerster took over the offensive line, and the Ravens gained 1637 (25th) yards rushing, and they surrendered 17 sacks (2nd). In 2007, they added 1797 yards on the ground (16th) and they gave up 39 sacks (21st).

At this first glance, Foerster looks like an average coach who struck gold on occasion, as his lines tend to perform similarly in his first year with each team to the production they contributed in the year before he came on staff. We're going to explore beyond the raw numbers to see if Foerster made any demonstrable impact on the units he was responsible for.

In 2010 and 2011, the Redskins maintained a respectable 4.2 and 4.0 yards per carry (16th and 22nd in the NFL), respectively, but had the second and seventh-fewest rushing attempts in the NFL. Their low rushing totals and high sack numbers were directly related to them having the fourth and fifth-most passing attempts in the league, while Shanahan tried to convince himself that he could win big with an aging Donovan McNabb and erratic Rex Grossman at QB. Prior to Foerster's first year, the Redskins had given up the same number of sacks with 2 less passing attempts.

In 2012, the Redskins added Robert Griffin III and Alfred Morris to their roster, and they led the league in rushing and averaged an impressive 5.2 yards per carry, while attempting less passes than all but two teams in the NFL. The huge jump in production can be attributed to having a much better running back (Morris is better than Ryan Torain and Roy Helu, a guy who couldn't crack the 49ers 90 man roster after a tryout), and getting over 800 yards from the QB position, but the basic numbers still don't tell the whole story. In 2010, the Redskins offensive line lost 13 starts due to injury. In 2011, the offensive line lost 18 starts due to injury. In 2012, only one start was lost due to injury along the offensive front. In 2013, zero starts were lost to injury.

While protecting his rookie QB (from interceptions, not injury), Shanahan had his offense attempt the second-most running plays in the league and the third-fewest passing plays. That the Redskins still gave up 33 sacks on so few passing attempts is not encouraging. Looking at the roster, it appears that Foerster was doing solid work with a unit that boasted a very talented left tackle (Trent Williams), but offered late round and undrafted journeyman talent along the rest of the line Kory Lichtensteiger, Will Montgomery, Chris Chester, and Tyler Polumbus.

2014 was a giant statistical step back, but Foerster's unit again maintained a solid yards per carry average (4.2 yards). Jay Gruden's first year at the helm featured three different starting quarterbacks (Griffin, Kirk Cousins, and Colt McCoy), all of whom frequently had to throw in obvious scenarios, as the team was consistently playing from behind, presenting obvious opportunities for pass rushers and greatly limiting rushing attempts (their 401 attempts were 21st in the NFL). Predictably, the sack numbers increased dramatically.

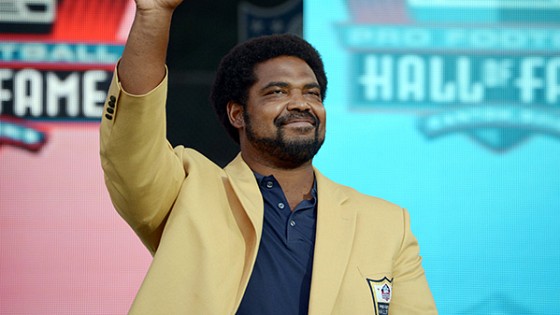

Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports

The two seasons (2008-2009) Foerster spent in San Francisco must have been among the most frustrating of his career. With years of experience coaching the zone blocking scheme, he was asked by Mike Nolan and Mike Martz to get better production from a beat-up unit in a man/gap blocking scheme. That's like taking a dog with extensive training and years of experience serving as a seeing-eye dog and deciding that such a smart dog should be capable of sniffing for bombs or drugs. The dog would obviously be intelligent enough to learn and perform the task you've decided to assign to it, but all of its training and experience make it most qualified for a different task.

Foerster actually performed very well, under the circumstances. Working outside of his professional sweet spot, he also had to struggle to piece together a starting unit in a year where the 49ers' offensive line lost a staggering 37 starts due to injury (14 of which were by Jonas Jennings, who combined elite left tackle talent with connective tissues seemingly made of rice paper). The 49ers were last in the league in sacks, but Mike Martz insisted upon calling a grossly disproportionate number of long-developing pass plays with an injured and shuffled line, while starting Shaun Hill and the impossibly overwhelmed JT O'Sullivan at quarterback.

Martz also refused to allow his quarterbacks to audible out of his called plays, insisting that he had designed perfect passing plays that always had a correct adjustment for whatever the defense presented. It is not at all surprising to realize that Martz's offenses are always near the top of the league in sacks and quarterback hits. Considering that the 49ers had surrendered the same number of sacks the year before Foerster arrived, without 2008's tremendous mountain of injuries and Martz's insistence upon drop-back passing, it's easy to make an argument that Foerster actually improved the performance of the unit in his first year.

After the 2008 season, Mike Singletary fired Martz and eventually hired Jimmy Raye, who's presentation of Singletary's vision most frequently consisted of incorporating the man/gap blocking scheme on first and second down, then throwing the ball on third and long. Once again, Foerster's unit maintained a respectable average yards per carry (4.3; good for 12th in the league), even though teams appeared to always know when the run was coming. The unit cut down the number of sacks they surrendered to 40, which was much closer to the league average. He managed this task while once again coaching outside of his preferred skill set, all the while managing a roster that featured the likes of Chilo Rachal and Adam Snyder as starters for 15 and 16 games, respectively.

In Baltimore, Brian Billick leaned heavily upon Rex Ryan's defense to dominate games, and he employed an offensive strategy of trying to score just enough points to not lose games, while not taking offensive risks that could result in turnovers or bad field position. 49er fans are likely familiar with this offensive approach from the last decade of defense-driven football. Foerster arrived to help a struggling offense that was averaging 3.6 yards per carry while sitting in the bottom third of the league in pass protection. While the yards per carry average actually dropped to 3.4, Foerster helped the line cut the number of sacks they allowed to 17, which was less than half of the previous year's sack total.

Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports

Foerster managed this feat with a unit composed of aging star Jonathan Ogden and two late round draftees and two undrafted linemen. Jamal Lewis had begun to succumb to the injuries and tremendous workload he accumulated earlier in his career, having carried the ball over 300 times in each of his first six seasons in which his starts were not limited by injury.

In 2007, Lewis was replaced by Willis McGahee, and Foerster got to break in two impressive rookies on the right side: RG Ben Grubbs and RT (at the time) Marshall Yanda. Even as the rookies learned their craft and the offense adjusted to new terminology and tendencies from new OC Rick Neuheisel (who only lasted one year), the rushing yards per carry increased to 4.0. The rotating QB roster of Steve McNair, Kyle Boller, and Troy Smith, along with the steep learning curve for the rookie wall on the right side of the line, contributed to the line allowing a more pedestrian 39 sacks.

While extenuating circumstances, such as injury and changing offensive coordinators, cause occasional fluxuations in the trend, it appears that Chris Foerster has demonstrated moderate improvement in the production of each line he coaches, in each of his previous three stops. He does not appear to be one of the few truly exceptional coaches who can extract dominant play from substandard talent, but he seems adept at getting his units to play up to and occasionally slightly above their potential and circumstances.

In recent 49er memory, he compares favorably to Vic Fangio, a well-traveled, intensely knowledgeable coach who is able to succeed with sufficient talent. Foerster's success in Baltimore (while Fangio was the LB coach, coincidentally enough), getting two rookies up to speed and improving the line at the same time, should be encouraging for 49er fans who can reasonably expect at least two positions on the line to be filled by players who have not started at those positions with the 49ers previously. Fans should also be encouraged by the likelihood that the 49ers currently have as much talent in their current OL unit as Foerster has presided over in his coaching history.

Kyle Terada-USA TODAY Sports

49er fans should expect the team to continue to run the ball well, with a greater number of zone running plays. If the unit remains healthy, the yards per carry average should increase as the unit gains familiarity with one another and their respective roles and tendencies, and pass protection should improve markedly from last season. If the 49ers suffer injuries on the line, fans should expect Foerster to help the unit weather that storm well, as his units have maintained respectable ypc averages through injury-ravaged seasons in the past.